How to be a better, happier investor

Recording artist Daniel Powter was having a bad day - for much of the

summer of 2006. At least that's what his popular song told the world.

Anyone who has invested in the stock market can sympathize because

they, too, have probably seen their fair share of bad days.

The market's gyrations give nearly everybody a case of emotional

whiplash. One trick to succeeding as a long-term investor is learning

how to reduce the inevitable psychological swings.

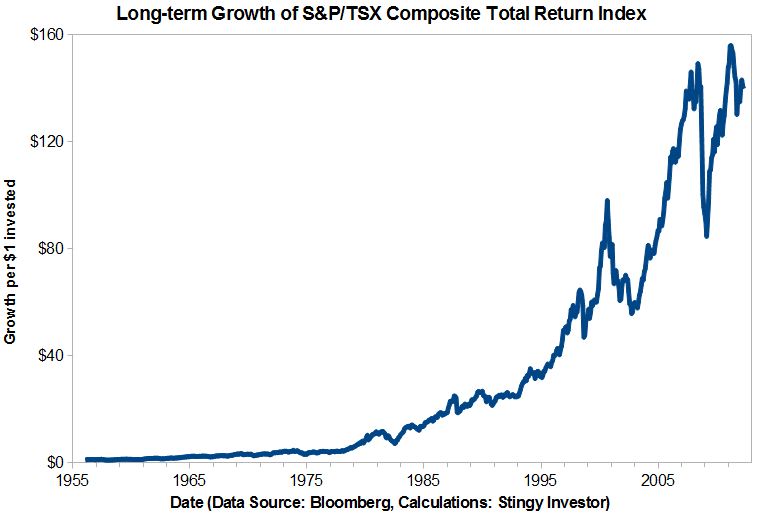

The accompanying graph shows the growth of the S&P/TSX composite index

(with dividends reinvested). As you can see, the long-term has been

highly favourable to Canadian stock investors. Even the last couple of

decades - which have seen a few grisly bear markets - turned out okay

for patient cost-conscious investors.

[larger version]

If the long-term returns from stocks have been good, why can it be so

hard for investors to sleep tight? It comes down to psychology. We

feel the sting of losses about twice as strongly as we feel pleasure

from gains. This quirk of the human mind is called loss aversion and

was demonstrated by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, two of the

pioneers of behavioural finance.

The emotional toll exacted by loss aversion can cause problems when

you track every twitch of the markets. After all, the chance that

stocks will rise, or fall, on any given day is about equal. But since

losses lower happiness much more than gains boost it, following the

market's day-to-day fluctuations becomes a recipe for depression.

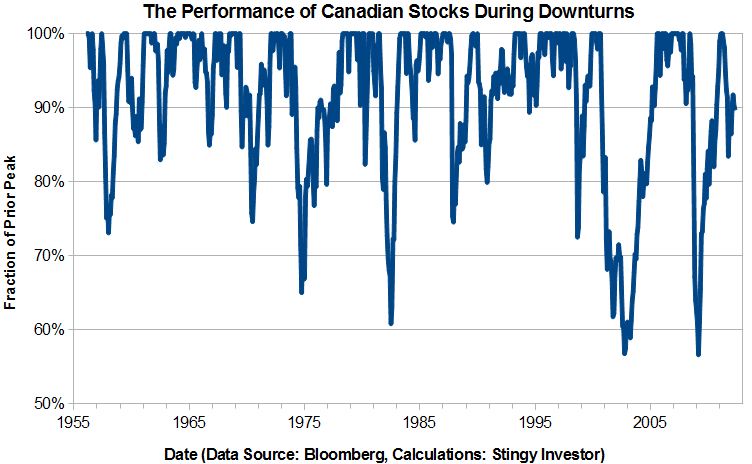

Matters become worse if your memory is good and you notice when your

portfolio reaches new highs. While it can be fun to see your wealth

climb to new peaks, portfolios often trade well below their former

highs. This is amply demonstrated by the other graph, which shows down

periods for the S&P/TSX Composite total return index. More often than

not, stocks are depressed when measured against their former highs.

[larger version]

The upshot of all this is that you should mentally prepare yourself

for the overwhelming likelihood that, as a stock investor, your

portfolio will see a great many bad days even if your long-term

results are good. Indeed, you'll likely spend much of your life with a

portfolio that has declined from its prior peak.

Mental discomfort is the price you pay to obtain good

returns. Unfortunately, few investors are actually prepared to pay

that price in practice.

If you were scared out of the markets near the lows of 2001 or 2009

then investing in stocks is probably not for you. (Think of the

experience as an important - and likely expensive - lesson. And be

sure to remember it.)

But even those with stronger stomachs should resist the urge to look

at their portfolios every day. It's a recipe for unhappiness that may

prompt you to play Mr. Powter's song far too often.

First published in the Globe and Mail, May 18 2012.

|

|