The scourge of inflation

Inflation is the silent killer of retirement dreams. It sneaks in over

the years and nibbles away at nest eggs, leaving people poorer than

they once thought.

How does it do the dastardly deed? By reducing the purchasing power of

money over time.

You can see its impact in the rising prices of many goods and services

over the past few decades. A generation ago you might have been able

to buy a nice home for $50,000; the same house today might set you

back $250,000.

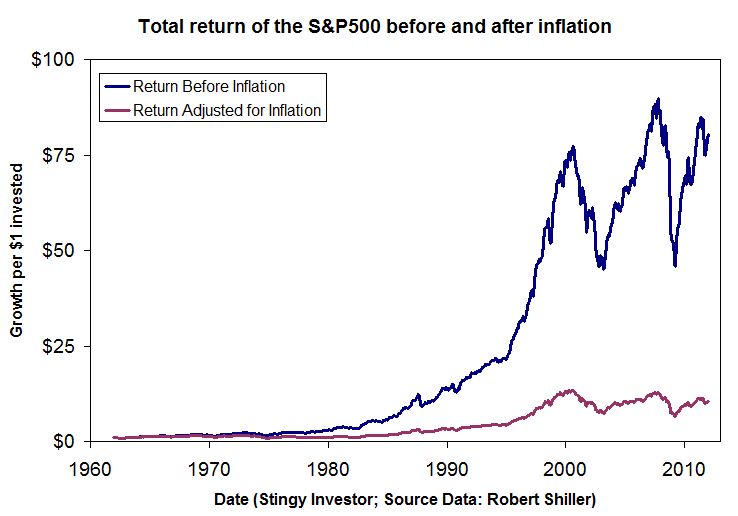

To see the bite inflation can take out of your retirement plans, let's

start with the happy picture you may have spotted at your financial

advisor's office. It's the graph showing the long-term returns of the

S&P500.

Sure the index bounces around, but the overall picture, as depicted in

the accompanying graph, is mighty impressive. The index managed an

average total return of 9.2 per cent a year since the early 1960s,

which sounds more than big enough to satisfy most investors.

[larger version]

But that figure doesn't account for the impact of inflation. After

that sneak thief had his way, the return pattern follows the much

lower line on the graph. Your inflation-adjusted return would have

amounted to an average of only 4.8 per cent a year.

If you hadn't properly adjusted for inflation, you might have spent

too much early in retirement based on the high dollar returns and been

left with too little purchasing power later on.

Inflation doesn't work alone. It does its dirty work in combination

with partners, like taxes and fees, that can take additional bites out

of your results.

Start with that 9.2 per cent return, take out a 2 per cent fee for the

management of your mutual funds, pay a quarter of the gains in tax,

and then see inflation run at 4.1 per cent and you're left with a

return of about 1.3 per cent. That's not much to live on despite the

market's very good return before all of these factors are taken into

account.

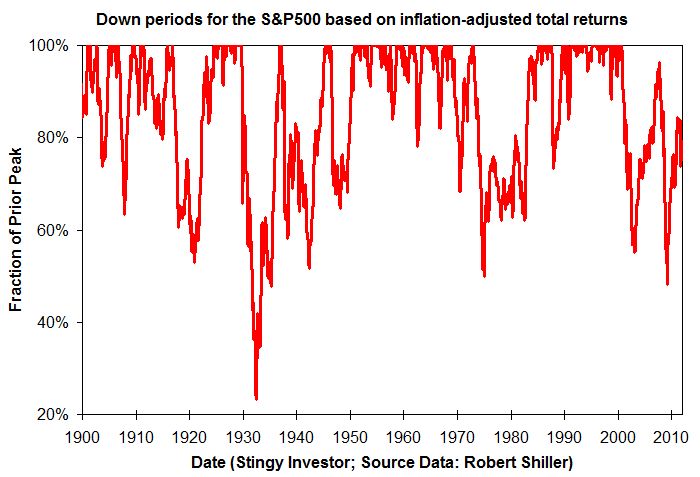

Even worse, the market can go into prolonged swoons, where

inflation-adjusted returns fall below even these modest levels. Since

the S&P 500 peaked in 2000, returns have actually been negative. There

are also other similarly long periods when the index declined in value

after adjusting for inflation.

You can see the sorry history in the accompanying graph which shows

declines in the inflation-adjusted index from its prior peak

level. While we are now in one such period, the 1970s and the 1930s

weren't much fun either.

If the current downturn persists for a few more months, it will

eclipse the 1973 to 1985 malaise in duration. Is it any wonder that

more and more people are postponing their retirement these days?

[larger version]

First published in the Globe and Mail, January 14 2012.

|

|